The Japanese Attack. In 1937 Japan attacked China and quickly captured the five provinces east of the Yangtze River, including the capital city of Nanking where the Japanese Army slaughtered hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians. The "Rape of Nanking" was widely publicized in the United States and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began pressuring the Japanese to withdraw from China. However, over the next few years the conflict in China deteriorated into a bloody war of attrition with little progress on either side, giving rise to the idea that if the Japanese could not defeate the poorly trained and equipped Chinese Army, they certainly posed little threat to the United States.

Hawaii, the Philippines and Alaska were U.S. territories, protected by the United States Army and Navy. For American military personnel, assignments in the tropical islands were welcome tours of duty. Mid-level officers such as Major Frank Loyd and Captain Arthur Noble were able to staff their homes with servants, tend to sporting events, and lead an enviable social life in the inexpensive and properous Philippines. The war in Europe was far away. Except for the war in China the Pacific region was quiet and peaceful.

Nazi Germany, meanwhile, had taken over most of Europe, threatening England by early 1941. President Franklin Roosevelt, bowing to popular opinion, vowed to keep the United States out of the European war.

But in July, 1941, the Japanese moved into French Indo-China (primarily Vietnam) to establish bases from which they intended to attack China from the rear. President Roosevelt, acting in concert with the British and Dutch governments, quickly embargoed all trade with Japan, an act that would cripple the Japanese Army and Navy due to lack of oil and supplies. He began building up General Douglas MacArthur's military forces in the Philippines--a direct threat to Japanese interests in the area. He sent an ultimatum to Japan: get out of China.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese delivered their answer--they attacked south, invading British Hong Kong, British Malaya, and the American Philippines, and they destroyed the American Navy at Pearl Harbor--all on the same day.

Bataan. General Douglas MacArthur commanded the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). His plan to defeat the invading Japanese at the beaches of Luzon Island failed completely when his poorly trained and understrength Philippine Army crumbled under the Japanese onslaught. Following the prescripts of War Plan Orange, he had his army retreat to Bataan Peninsula and nearby Corregidor Island where his troops, spearheaded by the Philippine Scouts, were able to hold out against the well trained and well equipped Japanese.  However, in the retreat he abandonded tons of supplies to the enemy and his soldiers were soon forced to subsist on a meager "Bataan ration" while the Japanese Army and Navy surrounded and blockaded them.

However, in the retreat he abandonded tons of supplies to the enemy and his soldiers were soon forced to subsist on a meager "Bataan ration" while the Japanese Army and Navy surrounded and blockaded them.

The USAFFE soldiers held out for four months, but eventually disease, starvation and lack of medical supplies devastated the men to the point that many of them could barely lift their weapons. In March, General MacArthur and a few of his staff escaped south to Australia. When the Japanese Army attacked in strength in April 1942, General Edward P. King, the U.S. Army commander on Bataan, was forced to surrender. On April 9, 1942, 70,000 American and Filipino soldiers became prisoners of the Japanese.

The Death March. Soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army had long been taught that they were racially superior to all other human beings, and that a patriot's lot was to die for his emperor or country. Their contempt for the defeated American and Filipino soldiers boiled over into one of the most horrible atrocities of modern wartime. 11,800 hungry, sick and emaciated Americans and 55,000 equally sick and emaciated Filipinos were forced to walk 65 miles up a highway to prison camp in the blistering tropical sun with almost no food or water. More than half of these men, the men who had fought America's first battle of World War II, were sick or wounded. Ten thousand of them needed hospitalization. Any falter on the part of a prisoner resulted in immediate execution. At first the Japanese guards shot any man who collapsed or fell out of line. Soon they resorted to bayonets, to save bullets. To maintain discipline, individual soldiers were singled out and tortured or bayonetted to death as examples. It is estimated that 8,500 of them died or were killed on the Bataan Death March, but no records were kept and Filipino civilians who witnessed the atrocities were told that they must never reveal what happened. For two years, the horrible treatment of the defeated USAFFE solders on the Bataan Death March remained a secret.

Camp O'Donnell. What the Bataan prisoners faced next was as bad or even worse. They were crammed into an overcrowded concentration camp, with little food and almost no medicine. Men died of diseases and starvation at an astonishing rate. Conditions in the camp were so horrible, and the death rate so high, that in July the Japanese Army sacked the camp commander, Captain Yoshio Tsuneyoshi, and shipped the American prisoners off to another, slightly less atrocious, camp. 1,460 of them had died in Camp O'Donnell. Over the next six months the surviving Filipinos were paroled to their home towns. But there were not so many of them left to go home. After only eight months in Camp O'Donnell, 26,000 of the 50,000 Filipino prisoners had died of their wounds, diseases and starvation.

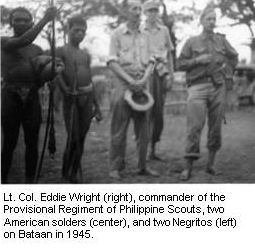

Escapees and Evaders. However, about 200 American soldiers had refused to surrender, and it is estimated that  another 200 escaped from the Death March. These men, including Private Pierce Wade and Lt. Col. Eddie Wright, slipped into the jungle to hide and await the return of General MacArthur and his army of reinforcements, believed to be en route from the United States. Sympathtic Filipinos harbored them, fed them, and kept them alive The Japanese hunted these fugitive Americans down, and half of them were captured, killed, or died of tropical diseases in the first few months after their escape. Some of the men, such as Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey, helped organize Filipino guerrilla bands hoping to help the war effort during the months they would wait. But the Japanese launched major crackdowns to eliminate the guerrillas. They offered handsome rewards to any Filipino who turned in an American, and they tortured and killed Filipinos who they suspected of helping fugitive American soldiers. Nonetheless, loyalty to the United States was widespread and many Filipino guerrilla organizations adopted fugitive American soldiers as their leaders.

another 200 escaped from the Death March. These men, including Private Pierce Wade and Lt. Col. Eddie Wright, slipped into the jungle to hide and await the return of General MacArthur and his army of reinforcements, believed to be en route from the United States. Sympathtic Filipinos harbored them, fed them, and kept them alive The Japanese hunted these fugitive Americans down, and half of them were captured, killed, or died of tropical diseases in the first few months after their escape. Some of the men, such as Lieutenant Edwin Ramsey, helped organize Filipino guerrilla bands hoping to help the war effort during the months they would wait. But the Japanese launched major crackdowns to eliminate the guerrillas. They offered handsome rewards to any Filipino who turned in an American, and they tortured and killed Filipinos who they suspected of helping fugitive American soldiers. Nonetheless, loyalty to the United States was widespread and many Filipino guerrilla organizations adopted fugitive American soldiers as their leaders.

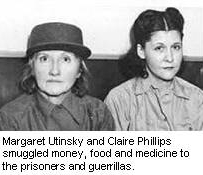

The Philippine Underground. The island nations of Southeast Asia accepted Japanese rule to a large degree, buying into "Asia for the Asians" after centuries of European colonial rule, in spite of Japanese cruelty.  But in the Philippines an underground resistance movement developed and Filipino, American and European patriots began smuggling badly needed food, money and medicine into the Japanese prison camps.

But in the Philippines an underground resistance movement developed and Filipino, American and European patriots began smuggling badly needed food, money and medicine into the Japanese prison camps.  Two American women and a cadre of Irish Catholic priests organized the biggest relief effort. Guerrillas in the southern islands made contact with General MacArthur through a few clandestine radios, and an intermittant flow of valuable military intelligence data found its way from the Manila underground to MacArthur's headquarters. The Japanese, however, soon developed counter-intelligence methods of their own, and they cracked down. By August of 1944, virtually every major underground leader and guerrilla leader on Luzon, the main island in the Philippines, had been captured and executed. But, once again, a few slipped away, and others stepped in to take their places.

Two American women and a cadre of Irish Catholic priests organized the biggest relief effort. Guerrillas in the southern islands made contact with General MacArthur through a few clandestine radios, and an intermittant flow of valuable military intelligence data found its way from the Manila underground to MacArthur's headquarters. The Japanese, however, soon developed counter-intelligence methods of their own, and they cracked down. By August of 1944, virtually every major underground leader and guerrilla leader on Luzon, the main island in the Philippines, had been captured and executed. But, once again, a few slipped away, and others stepped in to take their places.

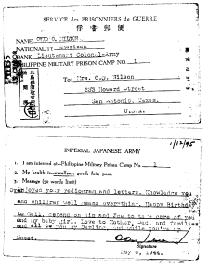

At home in the United States, families of prisoners of war had been notified of their men's status and once every six months they received a postcard, such as this one from Colonel Ovid O. Wilson. The postcards generally described the men's health as good and their living conditions at least tolerable. Virtually all of the U.S. Prisoners of War in the Pacific in World War II were the men who were captured at the beginning of the war on Bataan and Corregidor, plus 893 sailors and marines from Guam and Wake islands. Families of men who were not prisoners, men who were classified as Missing In Action, just waited, not knowing if their men were dead or alive. But ten prisoners led by Captain William Dyess escaped from a camp on Mindanao, and three of them were smuggled out of the Philippines by submarine and eventually brought back to the United States. In January 1944 they told their stories to the newspapers--stories of the Bataan Death March and of the horrible conditions at Camp O'Donnell and the other prison camps. Their families, the American government, and the world, were stunned. But what could they do?

At home in the United States, families of prisoners of war had been notified of their men's status and once every six months they received a postcard, such as this one from Colonel Ovid O. Wilson. The postcards generally described the men's health as good and their living conditions at least tolerable. Virtually all of the U.S. Prisoners of War in the Pacific in World War II were the men who were captured at the beginning of the war on Bataan and Corregidor, plus 893 sailors and marines from Guam and Wake islands. Families of men who were not prisoners, men who were classified as Missing In Action, just waited, not knowing if their men were dead or alive. But ten prisoners led by Captain William Dyess escaped from a camp on Mindanao, and three of them were smuggled out of the Philippines by submarine and eventually brought back to the United States. In January 1944 they told their stories to the newspapers--stories of the Bataan Death March and of the horrible conditions at Camp O'Donnell and the other prison camps. Their families, the American government, and the world, were stunned. But what could they do?

"Hell ships." As General MacArthur's forces approached the Philippines late in 1944, the Japanese loaded the Prisoners of War into cargo ships and sent them to Japan and Manchuria to work in coal mines and factories. The men of Bataan and Corregidor were packed into the holds of the ships so tightly that there was no room to sit or to lay down, and they had to take turns sleeping. They were given little food or water and no medical attention. The heat was so bad in the stifling, dark holds that men suffocated to death standing up. There were virtually no sanitary facilities and in some instances the Japanese would not even let the dead bodies be removed from the holds.

The ships were unmarked. Allied aircraft and submarines patroled the Pacific by 1944, and they attacked any Japanese ship they found. In an interview, Sergeant David Topping described to me the day that he and his buddies first heard the "ping" of sonar from a submarine. At first they did not know what it was, but a sailor in the group told them. Topping described how it felt standing there in the hot, dark hold of the ship waiting, waiting for the torpedo to hit. He prayed. As he waited he imagined what the explosion would be like, and the cold ocean water rushing into the hold. He prayed that the torpedo would hit their ship, and thus end their suffering.

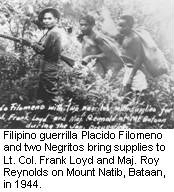

Guerrillas. The Philippine guerrilla movement continued to grow, in spite of Japanese campaigns against them. Throughout Luzon and the southern islands Filipinos joined various groups and vowed to fight the Japanese. The commanders of these groups made contact with one another, argued about who was in charge of what territory, and began to formulate plans to assist the return of American forces to the islands.  They gathered important intelligence information and smuggled it out to the American Army, a process that sometimes took months. General MacArthur formed a clandestine operation to support the guerrillas. He had Lieutenant Commander Charles "Chick" Parsons smuggle guns, radios and supplies to them by submarine. The guerrilla forces, in turn, built up their stashes of arms and explosives and made plans to assist MacArthur's invasion by sabotaging Japanese communications lines and attacking Japanese forces from the rear.

They gathered important intelligence information and smuggled it out to the American Army, a process that sometimes took months. General MacArthur formed a clandestine operation to support the guerrillas. He had Lieutenant Commander Charles "Chick" Parsons smuggle guns, radios and supplies to them by submarine. The guerrilla forces, in turn, built up their stashes of arms and explosives and made plans to assist MacArthur's invasion by sabotaging Japanese communications lines and attacking Japanese forces from the rear.

When General MacArthur returned to the Philippines with his army late in 1944, he was well supplied with information. It has been said that by the time MacArthur returned, he knew what every Japanese lieutenant ate for breakfast and where he had his hair cut. But the return was not easy. The Japanese Imperial General Staff decided to make the Philippines their final line of defense, and to stop the American advance toward Japan. They sent every available soldier, airplane and naval vessel into the defense of the Philippines. The Kamikaze corps was created specifically to defend the Philippines. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was the biggest naval battle of World War II, and the campaign to re-take the Philippines was the bloodiest campaign of the Pacific War. But intelligence information gathered by the guerrillas averted a bigger disaster--they revealed the plans of Japanese General Yamashita to entrap MacArthur's army, and they led the liberating soldiers to the Japanese fortifications.

One of the men who refused to surrender on Bataan was Lt. Col. Frank R. Loyd. During his three year ordeal in the Philippine jungles he was devastated by tropical diseases, threatened by natives who could turn him in for reward money, and hunted by the Japanese Army. Eventually he joined a guerrilla band headed by Corporal John Boone. Col. Loyd kept a daily diary which he hid in the jungle and largely recovered after the war. His wife, Evelyn, kept her own diary at home in San Antonio, Texas. Bataan Diary is based on the diaries of Frank and Evelyn Loyd, supplemented by five years of the author's research into the many events that occurred in the Philippines and central Pacific during World War II.

One of the men who refused to surrender on Bataan was Lt. Col. Frank R. Loyd. During his three year ordeal in the Philippine jungles he was devastated by tropical diseases, threatened by natives who could turn him in for reward money, and hunted by the Japanese Army. Eventually he joined a guerrilla band headed by Corporal John Boone. Col. Loyd kept a daily diary which he hid in the jungle and largely recovered after the war. His wife, Evelyn, kept her own diary at home in San Antonio, Texas. Bataan Diary is based on the diaries of Frank and Evelyn Loyd, supplemented by five years of the author's research into the many events that occurred in the Philippines and central Pacific during World War II.

| Sponsored links: |

| Park City ski condo rental |

|

Forgotten Soldiers movie |

Philippine  Scouts Heritage Society

Scouts Heritage Society |